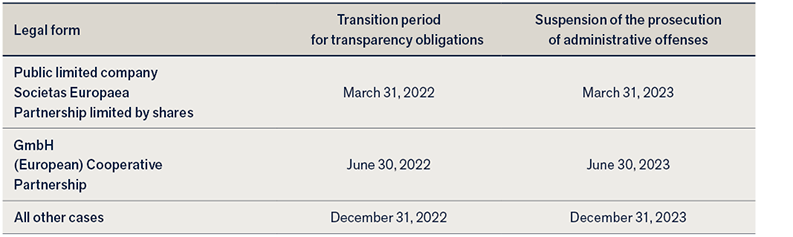

If obligated parties discover discrepancies within the scope of their due diligence obligations, they must report these promptly to the register-keeping body. In the case of discrepancies relating to undertakings that were previously able to invoke a notification fiction, the reporting obligation - across the board for all legal forms - will not apply until April 1, 2023. This is intended to avoid “unnecessary compliance expense”.[27] It should be noted, however, that this transitional regulation also does not apply to newly established undertakings.

IV. Inspection

The Transparency Register can be inspected by certain authorities, obligated parties under the Money Laundering Act as well as all members of the public. The TraFinG now clarifies - for data protection reasons - that inspections by authorities may only be carried out for the fulfillment of statutory duties and that inspections by obligated persons may be carried out exclusively for the fulfillment of due diligence obligations.[28] In other respects, it remains the case that the possibility of inspection can be restricted at the request of a beneficial owner. For this purpose, the person concerned must show an interest worthy of protection within the meaning of Section 23 (2) sentence 2 MLA. He or she may also request information on which members of the public have inspected the documents.[29]

V. Fining regulations

The TraFinG does not substantially change the provisions on fines. As before, violations of transparency obligations can be punished with a fine of up to EUR 150,000 if committed intentionally, and otherwise with a fine of up to EUR 100,000. In the case of serious, repeated or systematic violations, fines of up to EUR 1 million or up to twice the economic benefit derived from the violation are also possible. If such violations are committed by certain obligated parties (e.g. credit institutions, insurance companies), they may be subject to fines of up to EUR 5 million or up to 10% of the total turnover.

VI. The FAQ of the Federal Office of Administration (“Bundesverwaltungsamt”)

The Federal Office of Administration regularly publishes guidance on the Transparency Register.[30] Even though they are not legally binding, practice is almost always guided by them. Most recently, they caused some confusion with regard to indirect shareholdings. In the meantime, however, it should be clear (again) that an indirect beneficial owner generally[31] only exercises control within the meaning of Section 3 (2) sentence 2 MLA if he holds more than 50% in the intermediate company (B) and the latter holds more than 25% in the company (A). The TraFinG does not provide for any changes in this regard.

VII. Summary

Observing transparency obligations has always been part of corporate compliance. With the TraFinG coming into force, their importance is growing suddenly: From August 1, 2021, many legal entities will have to make a notification for the first time. In groups with a large number of undertakings, this will entail a high administrative burden. For obligated parties under the Money Laundering Act, on the other hand, the change in the law may make it easier for them to fulfill their due diligence obligations.

In parallel, Germany also transposed the Sixth Money Laundering Directive[32] in March 2021. It does not provide for any changes with respect to the Transparency Register, but concerns the criminal offense of money laundering. Without being obliged to do so by European law,[33] the legislator has significantly extended the scope of the money laundering offense. According to the new section 261 of the Criminal Code (“StGB”), it is no longer merely a selective catalogue of predicate offences that can be the starting point for a money laundering offence, but any unlawful act (so-called “all crimes” approach). For obligated parties under Section 2 of the MLA, the tightening of the criminal offense also increases the scope of the reporting obligations under Section 43 of the MLA, although the legislator considers the actual compliance costs to be low.[34]

[1] Law on the Implementation of the Fourth EU Money Laundering Directive, the Implementation of the EU Money Transfer Regulation and the Reorganization of the Central Financial Transaction Investigation Authority of June 23, 2017.

[2] Section 19 (1) of the Money Laundering Act.

[3] BT-Drs. 19/28164, p. 48.

[4] Section 19 (2) in conjunction with. Section 3 MLA.

[5] Section 3 (3) no. 6 MLA-E.

[6] Section 20 (1) sentence 2 MLA-E.

[7] Section 20 (1) sentence 3 MLA.

[8] Section 10 (9) sentence 4 MLA; BT Drs. 19/28164, p. 49.

[9] BT Drs. 19/27635, p. 2 f.

[10] Section 47 (2) GBO-E; BT Drs. 19/27635, p. 206 f.

[11] Cf. Section 3 (2) MLA; section 20 (2) sentence 2 MLA old version.

[12] BT-Drs. 19/28164, p. 49 f.

[13] BT-Drs. 19/30443, p. 73.

[14] BT-Drs. 19/28164, p. 49 f.

[15] Cf. Directive (EC) 2004/109 of 15 December 2004.

[16] In this respect, also the statement of the German banking industry on the draft bill of the TraFinG of 18 January 2021, p. 5 ff.,

https://die-dk.de/media/files/210118_DK_Stellungnahme_zu_TraFinG_Gw.pdf (accessed July 20, 2021).

[17] Directive (EU) 2015/849 of 20 May 2015.

[18] Section 20 (2) in the version prior to the TraFinG.

[19] Directive (EU) 2018/843 of May 30, 2018.

[20] BT-Drs. 19/28164, p. 3 f.

[21] Section 11 (5) MLA-E.

[22] The register-keeping body of the Transparency Register is Bundesanzeiger Verlag GmbH, cf. Section 1 Transparency Register Award Ordinance of June 27, 2017.

[23] BT-Drs. 19/30443, p. 24 f.; Section 20a MLA-E.

[24] BT-Drs. 19/28164, p. 33. However, listed companies will be included here, see above under point I.3.

[25] Section 15 Commercial Code (“HGB”).

[26] Section 56 (1) nos. 55-66 MLA.

[27] BT-Drs. 19/28164, p. 58.

[28] Section 23 (6) MLA-E.

[29] Section 23 (6) MLA = Section 23 (8) MLA-E.

[30] https://www.bva.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Aufgaben/ZMV/Transparenzregister/Transparenzregister_FAQ.html (accessed July 20, 2021).

[31] In individual cases, however, veto or objection rights can lead to a dominant influence, cf. BVA, Questions and Answers on the Money Laundering Act (MLA), as of February 9, 2021, p. 13 et seq.

[32] Directive (EU) 2018/1673 of 23 October 2018.

[33] The Directive contained only minimum requirements, cf. Art. 1 para.1 Directive (EU) 2018/1673.

[34] BT-Drs. 19/24180, p. 25 f.